The Bridging Institute of America

A Non-profit Educational Resource for Professionals Employing the Bridging Method of Construction Project Delivery

How Bridging Works

Bridging is a construction project delivery method designed to reduce the Owner's risks and costs in quality construction.

Download a PDF of this information

The Bridging method is a proven construction project delivery method. When properly carried out on behalf of the project Owner by qualified designers/managers, the Bridging method will not only lead to well designed end products but also to other significantly better results for the project Owner.

Those results:

- Provides Owner with firm construction price in about half the time and half typical design cost

- Usually saves 4-5% or more in cost for fully equivalent end product

- Dramatically reduces Owner’s exposure to contractor initiated change orders and claims

- Quicker fixes and less disputes for correcting ever present “bugs” in new construction

- Reduces the Owner's Design Consultant's exposure to professional liability claims

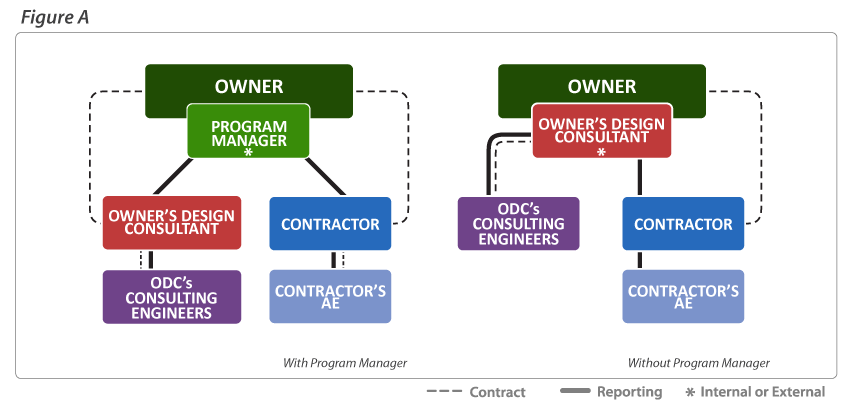

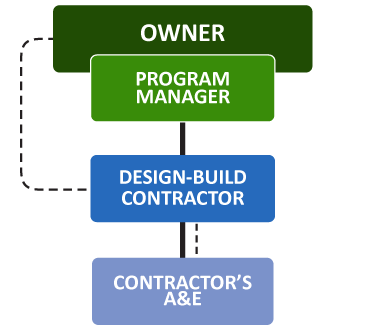

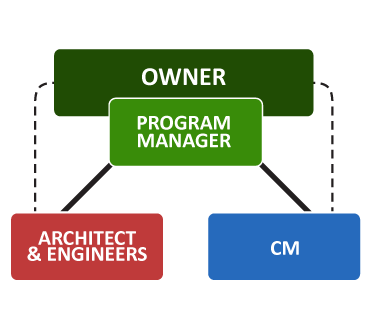

Shown below are two diagrams, both illustrating the way the key players are organized in a Bridging method project. On the left is a project in which there is a Program Manager. The diagram on the right shows a Bridging method project, but without a separate Program Manager.

Yet all of the above advantages for the project Owner are realized with Bridging without any loss of -

- Opportunity for creativity.

- Control of design.

- Control of design details.

- Quality of engineering.

- Quality of construction.

Construction also goes faster and smoother under Bridging, and project acceleration procedures work easily with this method.

A note on the “posture” of construction buyers: Relationship buying is clearly the best way to procure design and construction. In relationship buying the project delivery methods employed are not nearly as important as the relationships between the Owner and the architects, engineers, program managers and contractors. Relationship buying can work very well for private sector Owners who are constantly in the market for new construction with projects of a similar type in the same market areas. However, relationship buying can also be the worst and financially the most dangerous way of buying design and construction if the Owner believes it can rely upon relationships when, in fact, the Owner cannot or should not rely on relationships. Generally, those buyers who can, with confidence, rely upon relationships are limited to private sector Owners who are constantly in the market for construction. Bridging was developed for owners who cannot or should not rely on relationships, but also works well for both types of construction buyers.

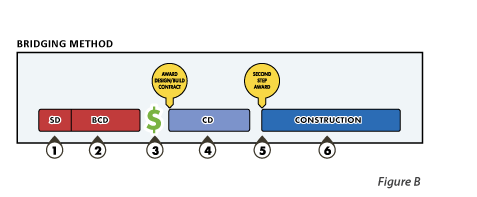

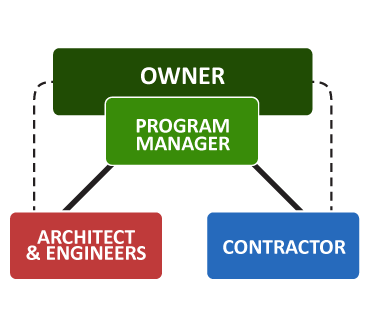

- Step 1: As illustrated in Figure B, a design team is selected as the Owner’s Design Consultant (“ODC”, sometimes referred to as the “Bridging Architect”, along with a Program Manager, or without a Program Manager; see Figure A). The ODC goes through Schematic Design in the same way an architect would do in traditional design services, with reviews and approvals by the Owner. Typically, the project budget and schedule would also be reconfirmed at this point (Figure B).

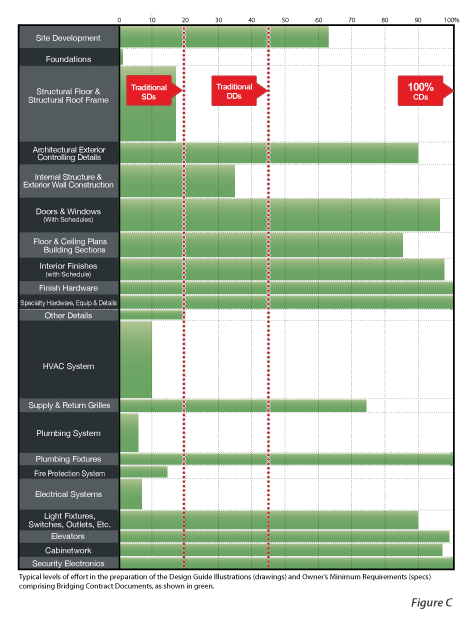

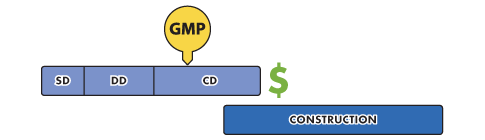

- Step 2: At first glance the chart below (Figure C) might seem to illustrate partially complete design. In fact, it illustrates very complete and advanced design and contract documents for the Owner’s agreement with a Design Builder for a typical project. In this phase the ODC with its consulting engineers as well as the Program Manager (if there is one) prepares the Bridging Contract Documents (“BCDs”). While this will typically require about the same level of effort as the preparation of Design Development documents in the traditional Design-Bid-Build method, BCDs are quite different from “DD” documents. They will be much more complete in many aspects, usually the architectural, and much less complete in others, typically some elements of the engineering. However, if the BCDs are properly prepared following Bridging methodology, the construction contract provides highly dependable protection of the design intent and of the contract price. In Bridging this is achieved with a design-build type of contract as opposed to a traditional construction contract, though Bridging is not Design-Build in the way Design-Build is typically carried out. These Bridging Contract Documents must fully protect the design, the quality, and the Owner financially, while allowing the proposing contractor as much latitude as is prudent in order to receive the best proposal.

- Step 3: The Owner can then receive competitive, fixed-price proposals based on the BCDs for the full project in a 2-step award contract. In this way the Contractor (who has its own architects/engineers by sub-contract or as employees) has the complete responsibility for both the construction and the final drawings and specifications and their being in compliance with the BCDs as well as for their completeness, accuracy and code compliance.

- Step 4: If the Owner is now ready to proceed, the Owner would then authorize the preparation of Construction Documents (“CDs”) by the Contractor and its AE. As this work proceeds the ODC will review these documents for compliance with the BCDs before authorizing payment.

- Step 5: Upon proper completion of the CDs, the Owner may proceed with the construction or terminate the contract with the Contractor without cause by payment for the CDs. The CDs then belong to the Owner. If Owner chooses to proceed, construction is authorized.

- Step 6: During construction the ODC and Program Manager (if there is one) would also represent the Owner with on-site observation of the work, seeing that construction is in compliance with both the CDs and the BCDs, authorizing the monthly progress payments and final payment to the Contractor.

Other Delivery Methods

Bridging solves problems that Owners often encounter with other project delivery methods, including the three most commonly used project delivery methods (“Design-Bid-Build”, “Design-Build” and “CM-at-Risk”) illustrated below. While all three of these methods have attractive aspects, they each have issues in terms of protecting the best interests of the Owner. The features and issues of each are discussed below.

Design-Bid-Build

Features: Logical and orderly process, well understood throughout the industry. Owner has a firm price based on complete contract documents before authorizing construction. Architect and Engineers have direct professional relationship with the Owner. There may or may not yet be a program manager.

Issues: Takes too long and costs the Owner too much to obtain a reasonably dependable total price. Method assumes that architects and engineers have the best knowledge of construction methods and costs, which is often not the case. Assumes that the Contract Documents (final drawings and specifications) are free of errors and omissions, which is humanly impossible.

Design-Build

Features: Contractor brings construction know-how to the design process from the outset and has full responsibility for both the design and the construction. There may or may not yet be a program manager.

Issues: There is a clear and serious conflict-of-interest between the Owner and the Architect and Engineers. A “Guaranteed Maximum Price” (GMP) issued on less than 100% complete working drawings and specifications is not contractually enforceable. Further, under this method it is often difficult for the Owner to obtain true competition on price for fully equivalent quality and details.

CM-at-Risk

Features: Contractor (“CM”) enters the process relatively early so as to provide costing, scheduling and construction method information to the Owner’s Architect and Engineers while design is still in development. Contractor is compensated by fee and obtains competitive prices from subs. Contractor provides a “Guaranteed Maximum Price” (GMP) at one or more points during the design process. There may or may not yet be a program manager.

Issues: As in Design Build, a GMP based on less than 100% complete drawings and specifications is not contractually enforceable and can be misleading to the Owner. In many cases there can be a conflict due to the “CM” using the same subs on other projects concurrently with the CM serving as traditional general contractor on other projects. CM-at-Risk also has the same “finger pointing” problem often experienced in Design-Bid-Build.